Grey Skies Porter – First Brew in Germany

Having moved to Germany with the intent of learning everything that I can about the art of fermentation, I absolutely needed to belly up to the bar and brew. Germany is obviously known for brewing and for their purity laws – Reinheitsgebot. Germany beer industry production makes it the fourth largest in the world; China taking the top spot at nearly five times Germany’s output. But Germany makes up for this by being number two in beer consumption per head, trailing the Czech Republic.

Finding beer in Germany is no problem; what I found surprising is the lack of local brewshops. Perhaps they exist and are simply well-hidden. There are homebrew regulations for German citizens; a German is permitted to make up to 200 liters per household per year (and one is supposed to notify local offices of each batch size and approximate alcohol content). This may explain some of my difficulties.

I ordered a slew of supplies from an online shop and opted to purchase whole, unground malt as I have access to a mill. (Note that this stone mill is intended for grinding fresh flour, so I took care to ensure a course meal so as not to end up with a powder.) The difficulty in buying online is that you end up buying in bulk. And who doesn’t like receiving a box in the mail with ten kilograms (22 pounds) of grains?

I approximate that I purchased malt and hops for at least ten brew sessions, but only yeast for four ten-liter (approximately two-gallon) batches. In other words, I purchased for two intended recipes and will brew on the fly with the remaining ingredients.

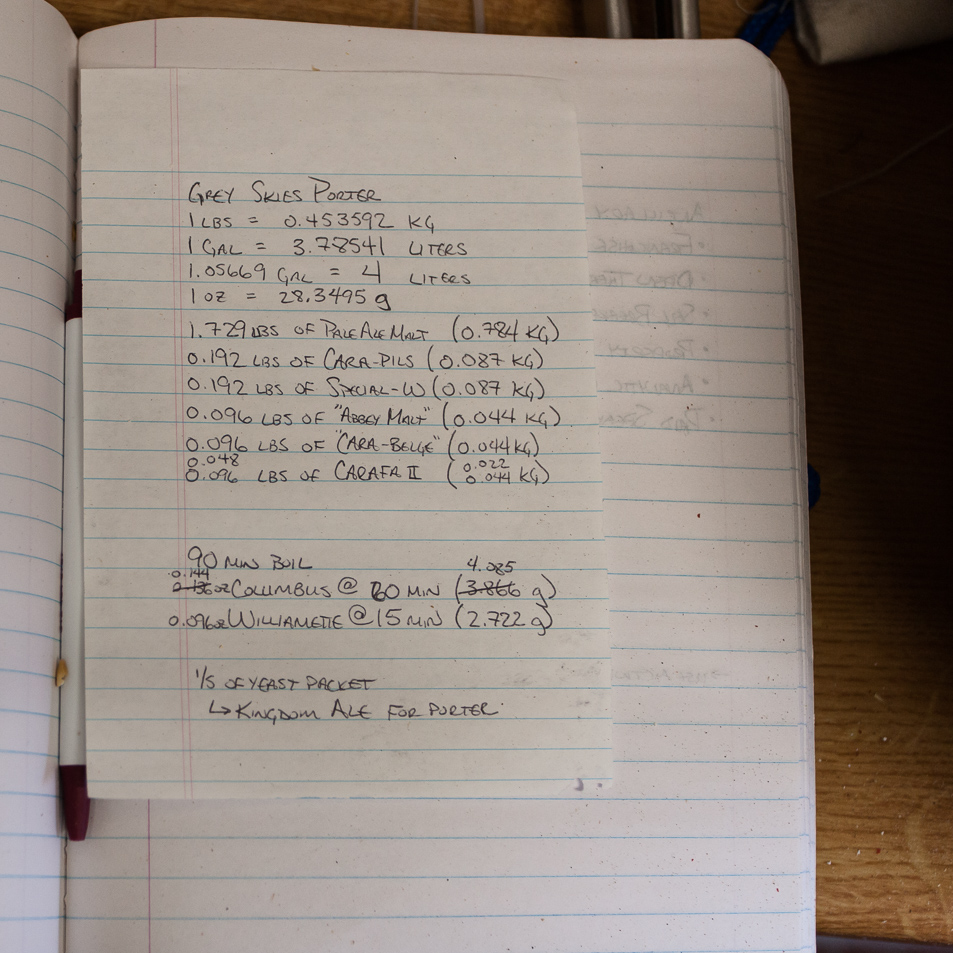

Grey Skies Porter

As is common for homebrewers, I found this recipe online. As a member of the American Homebrewers Association, I found this interesting full grain recipe on the website. But as is also common for those who brew at home, the ingredients suggested are never all in stock or even available, so I switched out some ingredients and dropped unnecessary ones. I also, as the picture shows, did some handy conversions to change the gallons to liters and the ounces to grams. Note that weighing ingredients is truly more accurate than using quantities…

I always opt for a full mash schedule, which consists of a dough-in, protein rest, beta rest, alpha rest, and the mash out. There are many forums that scoff at this quite time-consuming effort because the malting operations are now quite trustworthy that there truly is no need. However, the more I read about the enzymatic activity triggered by temperature and hydration, I feel I have more control over the process.

For this recipe, I opted for a slightly longer beta rest (40 minutes) and a shortened alpha rest (20 minutes). For those interested, these alpha and betas have nothing to do with those discussed with hops; rather, these are for the enzymes that break apart the starches into fermentable (and oftentimes tasty unfermentable) sugars.

After the mash out (i.e., achieving a temperature that stops all enzymatic activity), the grains are filtered out and the boil commences. Note that this is where I would have problems if I ground the malt too finely. Although in general the finer the grind, the greater the efficiency (i.e., more extractable sugar); a finer grind will also greatly increase a stuck mash (i.e., you just made bread dough, and no fluid will drain out of it).

While waiting for the sugar water to boil, this is where one drinks and contemplates life’s challenges. After which, you assign blame to the hops, which are then sacrificed to the boiling water in a ‘countdown to end of boil’ fashion. Unfortunately, the stove used did not get the water to a strong rolling boil, which may not have precipitated out everything needed to be precipitated (spoiler: the beer’s final flavor did have some off-characteristics).

After the boil, the challenge is to drop the temperature of the wort to room temperature (for an ale) as quickly as possible. In this case, it sat in an ice bath overnight. After a gravity reading of around 1.080, which was really high, yeast was added and left to ferment for two weeks.

When the fermentation ended, the beer was bottled and another gravity reading showed that the beer was unintentionally strong. When bottling, additional sugar is added for carbonation. There was no corn sugar available (a very easily fermented sugar), so a larger amount of white sugar was added to ensure carbonation (spoiler: not enough white sugar was added, and the beer was a tad flat). The beer was stored in bottles for another two weeks. [Yes, he’s wearing a headlamp…]

The Result

The Porter had the right color, but was slightly too hoppy, was a bit under-carbonated, and had a quickly-dissipated foam head. While the beer was drinkable, it was not quite quaffable. From my experience, the lack of a rolling boil and the substitution of white sugar were likely culprits. Rest assured, however, that this beer will not go to waste.

The copious notes and slight change in equipment will help in the future successful makes.